Chapter 5 Visual Search

5.2 Introduction

This chapter draws heavily on work by Nodine and Kundel (Nodine and Kundel 1987; H. L. Kundel et al. 2007; H. L. Kundel and Nodine 2004; H. Kundel and Nodine 1983; H. L. Kundel, Nodine, and Carmody 1978). The author gratefully acknowledges critical insights gained through conversations with Dr. Claudia Mello-Thoms ca. 2003.

To understand free-response data, specifically how radiologists interpret images, one must understand visual search. Casual usage of everyday terms like “search”, “recognition” and “detection” can lead to confusion.

Visual search is broadly defined as grouping and labeling parts of an image. In the medical imaging context visual search involves finding lesions and correctly classifying them (as benign or malignant).

A schema of how radiologists find perform the search task, termed the Kundel-Nodine search model, is described. This model is the basis of the radiological search model (RSM) described in Chapter 6.

5.3 Grouping and labeling ROIs

Looking at and understanding an image involves grouping and assigning labels to different regions in the image, where the labels correspond to entities that exist in the real world. As an example, if one looks at Fig. 5.1, one would group the image into 8 rectangular regions arranged in two rows and 4 columns and label them (from left to right and top to bottom in raster fashion): Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and the presidential seal. The accuracy of the labeling depends on expertise of the observer: if one were ignorant about American history one would be unable to correctly label them.

FIGURE 5.1: Grouping and labeling regions of an image.

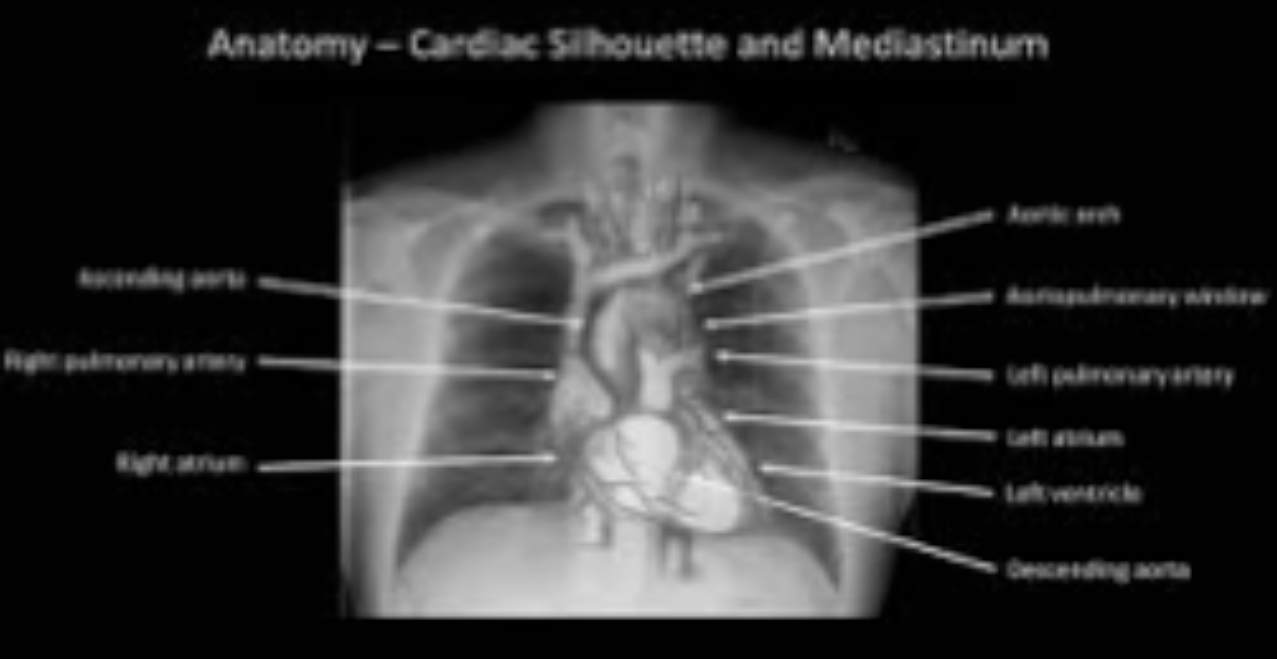

Image interpretation in radiology is not fundamentally different. It involves grouping and recognizing areas of the image that have correspondences to the radiologist’s knowledge of the underlying anatomy. Most doctors, who need not be radiologists, can look at a chest x-ray and say, “this is the heart”, “this is a rib”, “this is a clavicle”, “this is the aortic arch”, etc., Fig. 5.2. This is because they know the underlying anatomy, Fig. 5.3 and have a basic understanding of x-ray image formation physics that relates the anatomy to the image.

FIGURE 5.2: Grouping and labeling in radiology.

FIGURE 5.3: Correct grouping and labeling requires knowledge of the underlying anatomy.

5.4 Lesion-localization vs. detection

The process of grouping and labeling parts of an image is termed recognition. Recognition is distinct from detection, which is deciding about the presence of something that is unexpected or the absence of something that is expected, in other words, a deviation from what is expected. An example of detecting the presence of something that is unexpected would be a lung nodule and an example of detecting the absence of something that is expected would be an image of a patient with a missing rib (yes, it does occur, even excluding the biblical Adam).

The terms “expected” and “unexpected” imply expertise dependent expectations regarding the structure of a generic non-diseased image, which I term a non-diseased template, and therefore the ability to recognize clinically relevant perturbations from this template. By “clinically relevant” I mean perturbations related to the patient’s health outcome: recognizing scratches, dead pixels, artifacts of know origin, and lead patient ID markers do not count. Detection is the presence or absence of something, i.e., the perturbation, which could be anywhere. For example, in Fig. 5.1, recognizing a face is equivalent to assigning a row and column index in the image. Specifically, recognizing George H.W. Bush implies pointing to row = 2 and column = 3. Detecting George H.W. Bush implies stating that George H.W. Bush is somewhere in the image. Recognition is an FROC paradigm task while detection is an ROC task.

Instead of recognition (as used by Kundel and Nodine) I prefer the term “search”, as in “searching for and finding” a lesion.

5.5 Lesion-localization vs. lesion-classification

Since template perturbations can occur at different locations in the images, the ability to selectively recognize them is related to search expertise. 18 Lesion-localization expertise is the selective ability to locate clinically relevant perturbations that are actually present while minimizing false localizations.

Two important terms are introduced using FROC terminology:

Lesion-localization (or finding) expertise is the ability to find latent LLs while minimizing finding latent NLs.

Lesion-classification (or recognition) expertise is the ability to mark LLs while not marking NLs.

The skills required to find and recognize a nodule in a chest x-ray are different from those required to find and recognize a low-contrast circular or Gaussian shaped artificial nodule against a background of random noise (or even an anthropomorphic phantom). In the former instance the skills of the radiologist are relevant while in the latter they are not. This is the reason why having radiologists interpret random noise images and claiming that this somehow makes it “clinically relevant” is incorrect. One might as well use anyone with good eyesight, motivation and training. This paragraph also argues against phantoms as stand-ins for clinical images for “clinical” performance assessment. Phantoms are fine in the quality control context but they do not allow radiologists the opportunity to exercise their skills.

5.6 The Kundel - Nodine search model

The Kundel-Nodine model (H. L. Kundel et al. 2007; H. L. Kundel and Nodine 2004) is a schema of events that occur from the radiologist’s first glance to the decision about the image.

Assuming the task has been defined (and based on eye-tracking recordings obtained on radiologists while they interpreted clinical images) Kundel and Nodine proposed the following schema for the diagnostic interpretation process. It consists of two stages:

- Lesion-localization* or finding the locations of suspicious regions.

- Lesion-classification* or determining the classification (malignant or benign) of each found suspicious region.

5.6.1 Lesion-localization

The search stage is brief, typically lasting about 100 - 300 ms, which is too short for detailed foveal examination. Instead peripheral vision is responsible for identification of perturbations. The result is a global impression or gestalt, that identifies perturbations from the generic non-diseased template. It is remarkable that radiologists can make reasonably accurate interpretations from information obtained in a brief glance, see Fig. 6 in (Nodine and Kundel 1987). Perturbations are flagged for subsequent feature analysis, described below, in other words search tells the visual system where to look more closely. In the computer aided detection (CAD) context this stage is termed initial detection (Edwards et al. 2002).

5.6.2 Lesion-classification

Having found a set of suspicious regions the observer analyzes each region for evidence of disease: in principle he calculates the probability of malignancy for each region. In the CAD context this is termed candidate analysis, aka the feature analysis stage, where each region found by the initial detection stage is analyzed to calculate a probability of malignancy (and marked if the probability exceeds some algorithm-designer selected value).

An essential point that emerges is that decisions (to mark or not mark) are made at a finite, relatively small, number of regions. Attention units are not uniformly distributed through the image in raster-scan fashion; rather the global impression identifies a smaller set of regions that require detailed scanning.

5.6.3 Example

Eye-tracker recordings for a two-view digital mammogram for two observers are shown in Fig. 5.4, for an inexperienced observer (upper two panels) and an expert mammographer (lower two panels). The small circles indicate individual fixations (dwell time ~ 100 ms). The larger bright (high-contrast) circles are clustered fixations (cumulative dwell time ~ 1 s). These correspond to the latent marks defined in the previous chapter.

The large low-contrast circle is a mass (and so labeled) visible in both views.

The inexperienced observer finds more suspicious regions than does the expert mammographer but misses the lesion in the MLO view. In other words, the inexperienced observer generated more latent NLs but only one latent LL. The mammographer finds the lesion in the MLO (mediolateral oblique) view, which qualifies as a latent LL, without finding suspicious regions in other areas, i.e., the expert generated zero latent NLs on this case and one latent LL. It is possible the observer was so confident in the malignancy found in the MLO view that there was no need to fixate the visible lesion in the CC (craniocaudal) view - the decision to recall the patient had already been made.

FIGURE 5.4: Eye-tracking recordings for a two-view digital mammogram. The top row is an inexperienced observer while the bottom row is an expert radiologist. The left column shows MLO views while the right column shows CC views.

REFERENCES

A non-expert can trivially recognize any and all perturbations that may be present by claiming all regions in the image are perturbed.↩︎